Five-Lug Wheel, Brake & Suspension Conversion

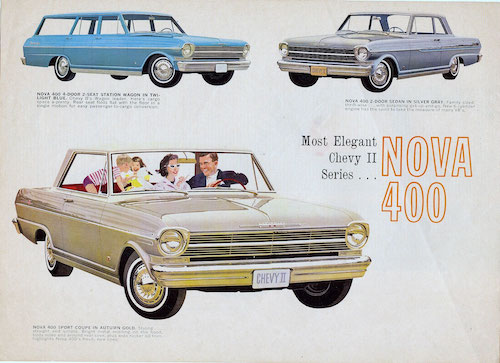

1962 - 63 Chevy II / Nova

Models: ALL

Body Styles: ALL

Contents

1. History

2. Why Do This?

3. The Conversion

3.a General Process

3.b Required Parts

4. Disclaimer!

History

The Chevy II debuted in 1962 with a new "high-mounted-coil, independent front suspension" mounted to a "body-frame integral design" construction (unitized front sub frame). The applied design of the front suspension was unique to the Chevy II. The general design (and a few parts) were pulled from other Chevrolets, such as the full size passenger cars. It was basically a mash-up of "tried and true" designs taken from other models to create a new platform, the "X Body", for vehicle production.

All 1962 - 63 Chevy IIs used four-wheel 9" drum brakes with a somewhat unique four-hole, 4 1/2" diameter bolt circle for the hub and wheel rim (hence the common phrase "four-lug"). 13" rims with a "new for 1962" two-ply tire design were standard, 14" rims were optional (RPOs 1796 & 1798) but uncommon. Over-size drum or disc brakes were not available, power brakes (RPO 403) and sintered-metallic shoe linnings (RPO 686) were however.

Steering was handled through a conventional relay rod type, rear steer linkage with a pitman arm, idler arm and fully adjustable tie-rods. Early unequal length tie rods and sleeves were shared with Chevy passengers cars. The idler arm was a completely new design unique to the Chevy II (and unique to 1962, subsequently being redesigned for '63). The steering gear (box) was a new compact recirculating ball type design, again unique to the Chevy II, with a 20-to-1 steering ratio and integral main shaft and worm gear. The power steering option (RPO 392) was based off the full size passenger car design, with some parts interchanging.

Rear suspension was of a conventional leaf spring design, but with a unique twist—mono leaf springs. Monos were advertised as giving the Chevy II a smoother or more "stable" ride. There is something to this as multi-leafs are often considered too stiff for such a light car. The rear differential was a soon to be outdated carry-over design from the 1950s passenger cars, adapted to the Chevy II. It was limited to three gear ratios and a rare limited slip option (RPO 676).

Quotes and specifications taken from original 1961 GM literature on the debut of the Chevy II.

Why Do This

The 1st and 2nd gen Nova's stock suspension and brakes leave a lot to be desired—the early four–lug setup is even worse. The brakes are smaller, the four–lug steering hub assembly weaker and replacement parts can be expensive, as well as hard to find. Most of the parts are unique to the 1962 - 63 Chevy II. The system was mediocre when new in the '60s—it is unacceptable for modern day driving, especially when converted to any flavor of V8 powertrain.

Restoring and maintaining a four–lug system is more difficult, expensive and time consuming than simply switching to the 1964 and later five–lug (which is of a standard GM design). These setups should only be retained when there is a compelling reason to, such as a one family car with sentimental value or exceptional "time capsule" survivor. If you are still on the fence as whether to convert or not, let's take a quick look at the system's drawbacks...

Brakes

Like so many other things on these cars, the four–lug brakes are basically unique to the Chevy II. For many years the brake system was considered obsolete by OEM parts manufacturers, eliminating the ability to purchase new components from your local parts house. Replacement brake parts had to be pulled from dwindling NOS and old aftermarket replacement stock (NORS). Good drums and complete rear axle bearings could be especially hard to locate. Brake parts are finally being reproduced, but as far as we know, they are produced overseas. They are also more expensive than the common five–lug brake parts, which can still be purchased from your local parts house (we use NAPA).

Rims & Tires

The four–lug hub bolt pattern is relatively unique, making rim and tire upgrades difficult. Add to that most Chevy IIs in this period had 13" rims. Running this setup one is severely limited in options, relegated to a shrinking offering of 13" or 14" wheel and tire combinations. Though aftermarket rims were available at one time, they have since become quite scarce. In contrast, the five–lug design uses a common GM bolt pattern giving you a variety of wheel options. A desire to upgrade rims and tires is often all that is needed to prompt one to junk the four–lug and make the conversion.

V8 Conversion

This is a "must do" upgrade if converting your Nova to a V8. The four–lug suspension was never designed to support a V8 setup or any kind of performance driving. The debut of both the small block V8 and five–lug suspension in 1964 was not a coincidence. Across American car manufacturers in this period V8 cars normally received a five–lug wheel and hub setup, while L6 and smaller motors used four–lug. There are instances of four–lug steering hub components failing in V8 converted applications.

Differential

The rear differential is an outdated carry-over design from the 1950s passenger cars, "shrunk" to fit the Chevy II. It has a center section (pumpkin) analogous to a Ford 9", but that is where the similarities end. The whole thing – housing, bearings, gears and axle shafts – are not of the common 10 or 12 bolt design most GM enthusiasts are used to. On top of that, most of the parts are unique to the early Chevy II and not reproduced (and probably never will be). Good used is not common, as most are scrapped without hesitation.

Factory available gear ratios were few (3.08, 3.36 & 3.55), with most cars having a 3.08 gear set. Though positraction was an option, we have only ever seen one unit. Aftermarket upgrades for the four–lug differential are virtually non-existent, so you are normally stuck running the gear set your car came with.

The Conversion

The conversion using stock parts is straightforward and can be accomplished in a day with hand tools most will have (plus a pickle fork or similar joint separating tool). A lift is not required (though makes things easier), but you will need to get the car off the ground and safely secured. This conversion will normally knock your wheels out of alignment, so make sure to plan for that. Finally, the big 1962 Chevy II shop manual is an invaluable resource for jobs such as this.

This is a great opportunity to rebuild the front suspension, since you will have it partially disassembled (check out our replacement suspension parts reference for GM & Moog part numbers). We also STRONGLY advise completely going through the brakes replacing the shoes, hardware, rebuilding wheel cylinders, etc. This is not a job to cut corners on.

It is not a bad idea to clean off the various mounting points (bolts, nuts, etc.) with a wire brush and soaking them with penetrating oil prior to getting started.

If not completely rebuilding the front suspension the upper control arms, coil springs and shocks can be left alone. They will stay in place and maintain their positioning if not unbolted. In this scenario the lower control arm, steering knuckle, hub and brakes can then be removed as an assembly. This is the process we outline below.

Required Parts

These are the parts required for the conversion. Everything can now be purchased new reproduction, but items like the steering knuckle and lower control arm are plentiful and best sourced from a donor car. Your local auto part store will carry the replacement brakes, bearings, seals and rubber brake lines.

- FRONT

- Steering knuckle & arm (the spindle assembly)

- Wheel hub and studs

- Hub castle retaining nut & special washer; bearing dust cap

- Brake dust (splash) shield

- Brake drum

- Brake shoes & all hardware

- Brake wheel cylinder and rubber line (steel are the same)

- Lower control arm (the four–lug control will work, but there are differences)

- Wheel rim & tire

- REAR

- Complete rear differential assembly—attaching components such as nuts, bolts and spring pads interchange

- Brake drums

- Brake shoes & all hardware

- Brake wheel cylinders

- Brake lines—

- Rubber – use the 1962 - 65 rubber hose

- Steel – use those meant for the axle application

- Park brake – cables interchange

- Wheel rims & tires

General Process

This is an overview of the five–lug conversion process, not an exhaustive walk-through. It assumes you are using stock GM components removed from a 1964 - 67 Chevy II and have the auto mechanical skills necessary to service suspension components. Our suspension torque specs reference will be helpful.

- Undue rubber brake line at subframe. Pre-soak this connection with penetrating oil and use line wrenches. This connection is often frozen. DO NOT FORCE—you will deform or snap the steel line!

- Separate & remove the tie rod end from steering knuckle arm.

- Remove the two bolts securing the strut rod to the lower control arm. If so equipped, remove the stabilizer (sway) bar end link from the control arm.

- Note or mark the position of the lower control arm eccentric bolt where it inserts at the subframe. This impacts your wheel alignment, so you want to get things back together as close as you can to how they were.

- Remove the bolt and eccentrics – may need to be carefully punched out of its bore. Tap lower control arm free from subframe (it can fight sometimes). Do not loose the bushing end caps! They need to be used on the replacement control arm.

- Place a floor jack under the brake drum, hub and knuckle assembly and lightly support the assembly.

- Remove the upper ball joint castle nut and separate the steering knuckle (spindle) from the upper ball joint, freeing the the steering knuckle assembly.

- You should now be able to remove the steering knuckle, hub, brakes and control arm as a complete assembly utilizing the floor jack—lower down and away.

- Reassembly with the five–lug unit is basically the reverse of this process. Make sure the end caps are on the lower control arm bushings, both sides. Torque everything to GM specs.

DISCLAIMER This information is provided as a courtesy to the Chevy II enthusiast. It is your responsibility to verify the safety and efficacy of these values and your related repairs. We are not in any way responsible for the success and / or safety of your vehicle repair. Nor are we liable for any bodily harm or property damage, to you or others, caused by faulty repairs. It should go without saying, but if you do not know what you are doing leave the engine, transmission & suspension work to experienced mechanics.